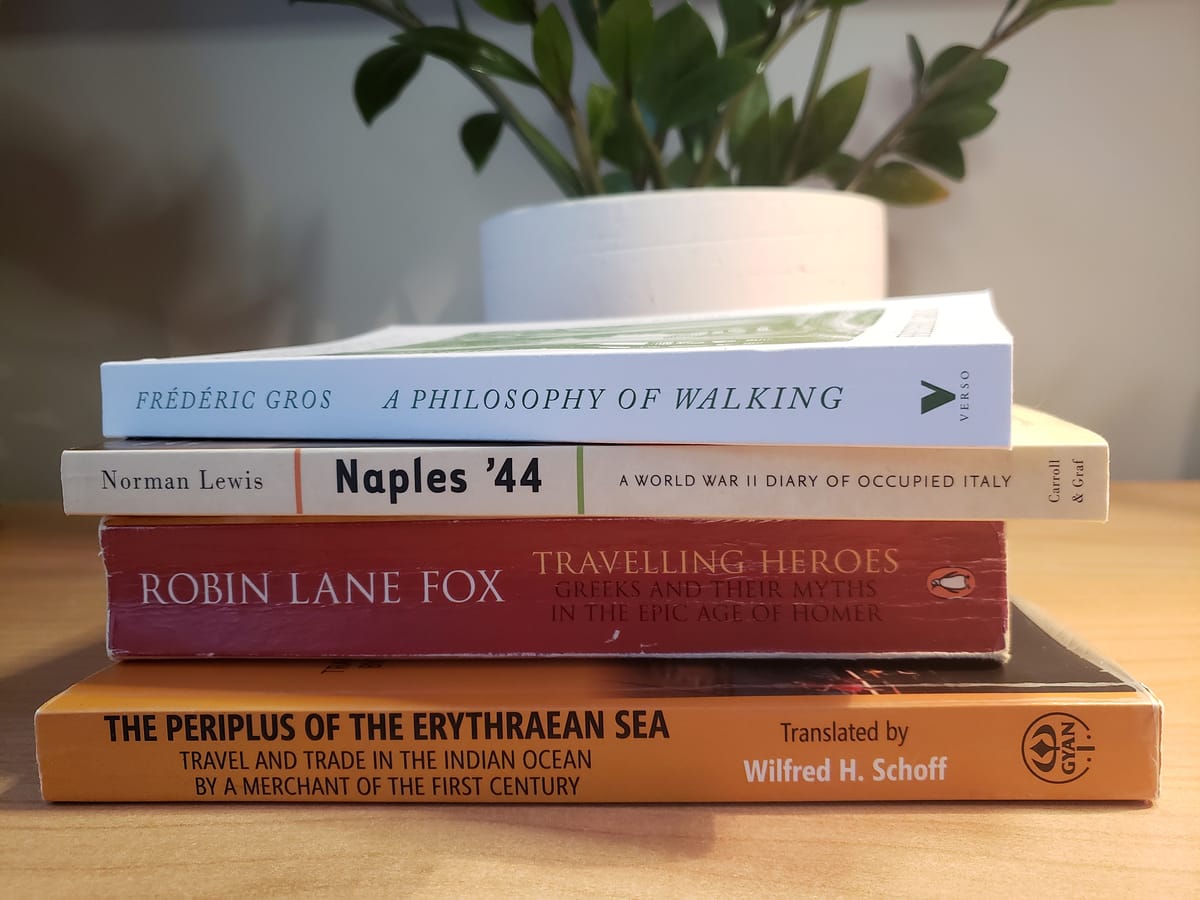

What I Read in 2024

As my first semi-productive year on Substack winds down, I'm taking the opportunity to look back at some of the books I read in 2024.

What I choose to read usually reflects what I’m thinking about, but my reading also leads me down new roads to new interests. I love learning about interesting authors and books from the footnotes or bibliographies of other books.

If there is any cohesive theme to my 2024 reading, it’s an effort to find lessons from the past that remain relevant today. I prefer to read older books, rather than new releases, because they pull me away from the doom-scrolling present. But since we are living in painfully interesting times, it can be all too easy to find ominous signs of doom. Let’s hope not all history repeats itself, or even rhymes.

This is not everything I read this year, but it’s a representative selection of four books I found worth thinking about again, that are not directly related to subjects I plan to write about in early 2025.

A Philosophy of Walking

By Frédéric Gros

(Originally published 2008)

This book caught my eye at a very nice new neighbourhood coffee shop-slash-book store I was trying to support. I bought countless coffees there, and one book, but the shop still failed to survive the year. The book, in a way, also failed me.

I consider myself an aficionado of walking. I get outside every day to cover a few kilometers on foot as I clear my head. For me, walking is the most practical and pleasant form of transportation for getting around downtown Toronto, and the cities we visit. I sold my last car two decades ago, and I’m not brave enough to ride a bicycle alongside homicidal SUV drivers, so walking is much more than a leisure activity in my world.

French philosopher Frédéric Gros, on the other hand, seems to almost entirely equate walking with the enjoyment of multi-day hikes in nature, albeit the sort of European nature where there’s always a cozy cafe or inn waiting at the end of the next leg. I’m certain Gros would be eaten by a bear if he attempted to hike Algonquin Park in Ontario. But I don’t get the impression he enjoys spending time exploring cities on foot, despite living in beautiful and walkable Paris.

While I have nothing against a scenic nature hike, much of the book is imbued with a lazy sort of anti-urbanism. A last-minute chapter on “urban flâneurs” redeems the author somewhat, but it comes a bit too late, as if some well-meaning proofreader had pointed out the bias and Gros had made a half-hearted attempt to atone for it.

I did, however, enjoy the book’s chapters that analyze the walking habits of famous philosophers. It turns out that deep thinkers as varied as Rimbaud, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Thoreau, Kierkegaard, Kant and even Gandhi put the act of walking at the center of their thought processes, each in their own way. These chapters, at least, gave me something to think about, and I’m keeping the book on my shelf mainly for those nice mini biographies of philosophers past.

Naples `44: A World War II Diary of Occupied Italy

By Norman Lewis

(Originally published 1978)

Norman Lewis was a prolific British writer, known for both his fiction and autobiographical non-fiction. In Naples `44 he writes about the time he spent in the British Army during the Second World War as part of the Allied invasion of Italy. This particular subject interests me because, as I have already written about, my paternal grandfather also participated in this operation as part of the Canadian troops fighting under British command.

Lewis’s book differs greatly from a typical war history in that it focuses only glancingly on the war itself: he writes very little about troop maneuvers, military strategies, battles, or the weapons used. Instead, he focuses on the humans who experienced the war alongside him: fellow military members, and the local Italians. As an officer in charge of intelligence, Lewis operates mainly behind the front lines as one of the only authority figures in a place where traditional government has collapsed. With limited resources, he uses his best judgement adjudicate between regular Italian citizens, business owners, local police, and fellow soldiers, helping them coexist in a time of enormous poverty and violence. Lewis soon finds that legitimate intelligence related to the war is exceedingly rare; but hearsay designed to benefit personal vendettas is painfully common.

The tone of the book is somewhat jarring: it is intensely irreverent, often sarcastic, and sometimes even darkly comic, and events frequently cross into the absurd. Lewis makes it clear from the beginning that he has little respect for the official narratives of the war, the motivations of political leaders, or the competence of those in command. But parts of the book are also very disturbing, and Lewis does not hesitate to describe in stark detail numerous instances where women and children are forced into sex work to survive, often by their own families. In one case, he takes over a command post from a departing Canadian officer who, Lewis soon realizes, had been a pedophile abusing local children in exchange for war rations.

Lewis is particularly adept at describing the impact of the war from an Italian perspective, particularly the instances where religion and history collide with modern realities. Scenes in which local priests fervently try to ward off encroaching lava from an erupting Mount Vesuvius by confronting it with crosses and religious icons of saints have stuck in my mind. This is a war book that manages to avoid even the smallest hint of glorification.

Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer

By Robin Lane Fox

(Originally published 2008)

A blurb on the cover of this book says it “reads as grippingly as any thriller,” but I have a duty to inform you that this is something of an exaggeration. There’s a lot of detail in this book, and it requires a fairly close read. To follow the narratives requires at least some understanding of two different things: ancient myths, and ancient geography. As a layperson and casual reader, my knowledge of both subjects is lacking, so I had to do additional external research (aka “Googling on my phone”) to make sense of some parts of this book. But, in the end, the effort was worthwhile.

Geographically, Travelling Heroes roughly outlines the spread of 8th Century BCE Greek peoples from Euboea (an island roughly 100 km northeast of Athens) through much of the Mediterranean world. Their travels took them eastward to what is now Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon; westward, to what is now Italy, Sardinia, Sicily, and Spain; and southward, to Crete and North Africa. At each destination the Euboeans set up trading colonies, some of which grew into towns and cities. But their habit of naming newfound places after locations back home with similar bays and mountains often creates geographical confusion, at least for the inattentive or tired bedtime reader (aka “me”).

As they journeyed, the Greeks encountered other peoples: Assyrians, Phoenicians, Etruscans, and numerous other smaller societies that were continually arising, merging, and disappearing as they conquered each other through the centuries. As the Greeks interacted with other cultures, they learned of their myths and legends, many of which were anchored to specific places. Ever adaptable, the Greeks frequently found parallels between their own mythology and that of others, and they were happy to adapt and expand their own narratives accordingly. This practice was applied to gods and heroes as varied as Poseidon, Adonis, Heracles, and Zeus. The oral histories of Homer, which Lane Fox dates to approximately this same 8th Century BCE time period, are also used as recurring reference points throughout the book — but if you’re looking for exciting tales about man-eating cyclopses and beautiful singing sirens, you will probably be disappointed.

In one example of the Greek’s mythological flexibility, a hero known to the Euboeans as Mopsus merges with the Hittite Muksas, and the Minoan Mo-Qo-So referenced in inscriptions at Knossos. Perhaps these mythical heroes were always one and the same, or perhaps they were different heroes later merged into one, or perhaps this is all simply etymological coincidence in the hands of overeager historians. “These neat conclusions are too optimistic,” warns Lane Fox at the end of one multipage theoretical exploration. While I find many of his connections fascinating, and his honesty refreshing, I’m sometimes also left wondering what to believe.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

Translated by Wilfred H. Schoff

(Originally published 1912)

A periplus is a type of ancient travel guide, and this particular Periplus describes a journey taken by a merchant sailor around the bodies of water now known as the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. The precise date of the journey is uncertain, but based on an analysis of the rulers and events the writer mentions, experts estimate the journey took place around 60 AD.

The edition of this book I obtained from Gyan (an India-based on-demand publisher) contains text translated and annotated by Wilfred H. Schoff in 1912. Although the book is nearly 300 pages long, only 27 of those pages are the translated text of the historical Periplus itself. The rest of the pages contain the introduction, analysis, and appendices written by Schoff, a Philadelphia-based scholar who died in 1932. Despite the fact that I was reading a century-old book describing events that occurred 20 centuries ago, I found the narrative and observations of the original Periplus writer compelling, and Schoff’s modernist clarifications and explanations enormously helpful (with the understanding that his historical interpretations and “modern” place names have probably evolved since 1912).

The ocean journey described in the Periplus begins in Egypt, and the original trader and author is presumed to have been an Egyptian Greek. The route first heads southward along the Arabian Gulf coast, hitting ports on the eastern edge of Africa as far south as a city called Rhapta, which some have identified as modern Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. The route then jumps back to the Arabian Gulf and continues eastward along the coast of what is now Yemen and Oman, touches on some sites in what is now Iran and Pakistan, and finally cuts across the Arabian Sea to the western coast of India. (The latter portion of the journey was only made possible after approximately 47 AD when the Greek navigator Hippalus discovered how to leverage the monsoon winds to travel directly across the Indian ocean, avoiding the much longer coastal route. References in the Periplus to this particular route are one of the factors that help to date it.)

For me, the most eye-opening lesson of the Peripulus is the amount of globalization already present in the world by 60 AD. My general understanding of history usually assumes that the peoples of the world were mostly isolated until the so-called Age of Discovery, when Western Europeans began aggressively exploring and colonizing the planet in the 1400s. But the Peripulus is a reminder that people have always looked beyond the horizon for goods and materials they could not obtain at home. Most interesting to me are the ancient trading connections between India and Africa. I was quite shocked to read that ghee — the clarified butter commonly used in Indian cooking — was routinely shipped to Africa 2,000 years ago. The direct ocean route is thought to have taken only 30 to 40 days during monsoon season, and with lactose and impurities removed, the pure fat in properly clarified ghee can remain edible for decades.

Other goods traded between the continents included incense components such as frankincense and myrrh; oils such as spikenard and palm oil; spices such as cinnamon; metals such as gold, iron, and copper; linens and fabrics for blankets and clothing; animal products such as ivory and tortoise shells; and consumables such as wheat, wine, and rice. Many of these goods could only be grown, harvested or otherwise obtained in very specific places, and their trade value increased with the distance from their origin. Goods often passed through multiple middle men, increasing in value each time. To protect profits, the exact origins of some substances were closely guarded secrets, carefully shrouded behind legends and rituals, and some sources remained unknown or misattributed for many centuries.

Travel at the time of the Periplus was very dangerous, with the risk of shipwreck, piracy or enslavement never far from the mind of sailors. In addition to describing the goods available for trade at different ports, the author of the Periplus was also careful to point out those areas that were particularly treacherous, or where the local inhabitants were known to be hostile. Nevertheless, he managed to survive his journeys long enough to write them down, and I’m glad he did, because the descriptions in this rare document make for fascinating reading 2,000 years later.

References

Gros, F. (2023). A Philosophy of Walking (Second Edition). Verso.

Gros, Frédéric. (n.d.). Verso. Retrieved December 30, 2024, from https://www.versobooks.com/en-ca/blogs/authors/gros-frederic

Lane Fox, R. (2009). Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer. Penguin.

Lewis, N. (2005). Naples ’44: A World War II Diary of Occupied Italy. Carroll & Graf.

Schoff, Wilfred H. – Persons of Indian Studies by Prof. Dr. Klaus Karttunen. (2017, May 10). https://whowaswho-indology.info/6039/schoff-wilfred-harvey/

Unknown. (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Translated by Wilfred H. Schoff. Gyan Publishing House.

Comments ()