We Tried That Already

Horrors once presumed safely in the past are returning to haunt us. Are we choking on our collective amnesia?

In my most prominent memory of my paternal grandmother, she is sitting at a linoleum table in her kitchen. She is rolling cigarettes on a small machine specifically devised for that purpose. My grandmother carefully fills a slot with pinches of dried tobacco from a metal tin, slides a cover shut, then pulls a lever. There’s a satisfying zip-zip-zip sound, and a cigarette pops out, perfectly stuffed and ready to smoke. She repeats this action dozens of times during our visit, her technique so practiced that she barely glances at the machine as she chats with us.

My grandmother died of throat cancer in her 60s, when I was a young teenager. My grandfather, a prolific cigar smoker, died of lung cancer a decade or so later. The residual smoke from their combined cigars and cigarettes permeated their home: after it sold, the new buyers tore it down and built a fresh, bigger house. I inherited some of my grandfather’s books, and after fifteen years on my shelf they still exude a cigar odour so strong that they trigger my allergies when I flip through them.

Meanwhile, young people are smoking again: real cigarettes, not vapes. Celebrities have been clambering over each other for a chance to glamorize the habit. Last year, Timothée Chalamet was chastised for smoking at a Beyoncé concert. More recently, Lady Gaga posed with a cigarette in a billboard ad for Die With A Smile, her new single. Some social media influencers are now promoting cigarette brands to their followers. They are called cigfluencers, a grotesque new portmanteau that proves even the most shameless of self-serving opportunists can always go lower.

The newest smokers shrug. It’s just an aesthetic, they say. The presumption that they can surely quit any time they want is left unspoken. With the number of active smokers at historic lows in recent years, anti-smoking advocates are hoping this cigarette resurgence is a blip, not a reversal of long-term trends. But other statistics are also showing that some vape users are graduating to cigarettes, an evolution long feared by experts.

Decades ago, my grandparents were far from alone in their prolific smoking habits. When I was a child, in the early 1980s, smoking was still common in public places. Shopping mall benches were crowded with smokers, and ashtrays were built into walls next to elevator call buttons. In elementary school, we molded ashtrays from clay in art class, and a cloud of smoke wafted from the teachers’ lounge every time the door opened, a detail The Simpsons got just right a few years later. When I attended university in the 1990s, some of the desks still had flip-top ashtrays integrated into their surfaces, though smoking was by then banned in lecture halls.

In my twenties, bars and restaurants in Toronto still offered smoking and non-smoking sections. The divisions between the two were often arbitrary, and it was not unusual to find smoke watering my eyes as I ate dinner at my supposedly non-smoking table. When a new craft beer bar opened that did not permit smoking, the idea was so novel the owners named it after the concept: Smokeless Joe.

I often used to see bands play at small Toronto music venues where the air was so thick with smoke that performers didn’t need fog machines to put on a light show. I’d return home at 2am and immediately shower, not wanting the clinging stench of smoke in my hair to transfer to my pillow.

You can probably tell I have little sympathy for today’s new smokers, and their naive attempt to romanticize a habit that is anything but. But I do have enormous sympathy for the smokers of my grandparents’ generation, those who grew up during the Great Depression and the Second World War, when the dangers of smoking were less understood.

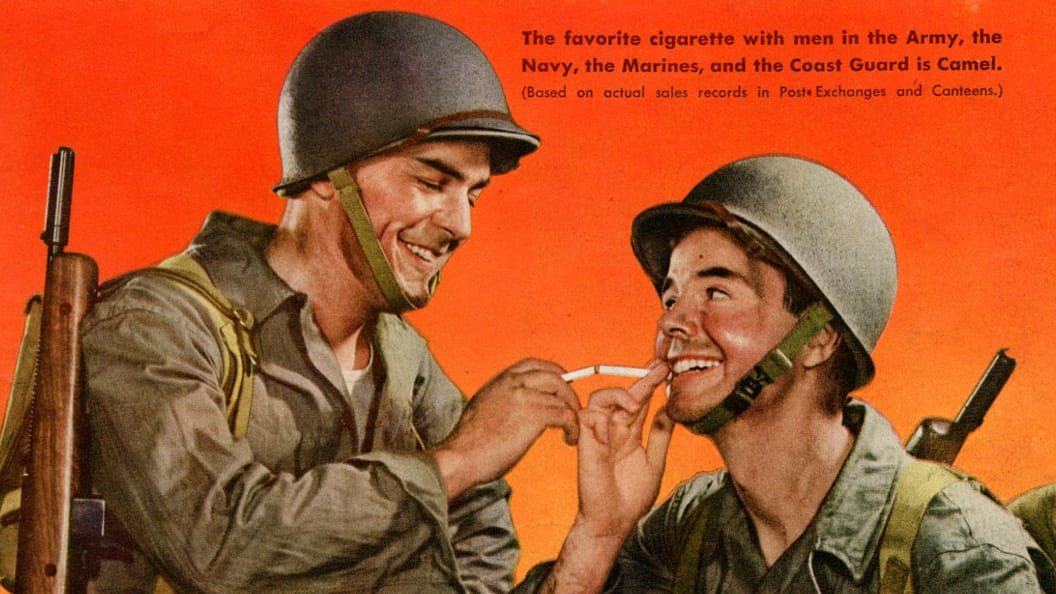

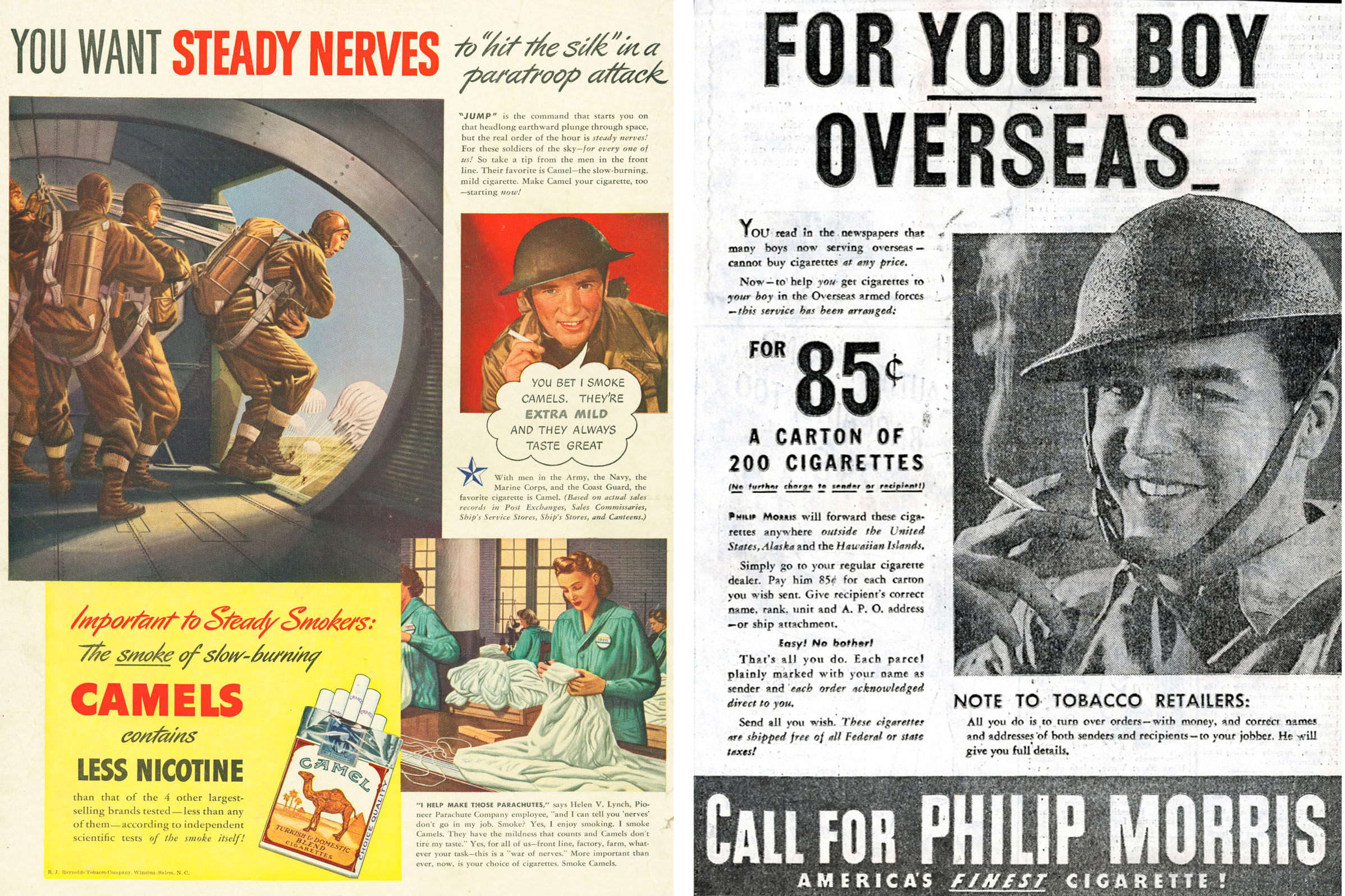

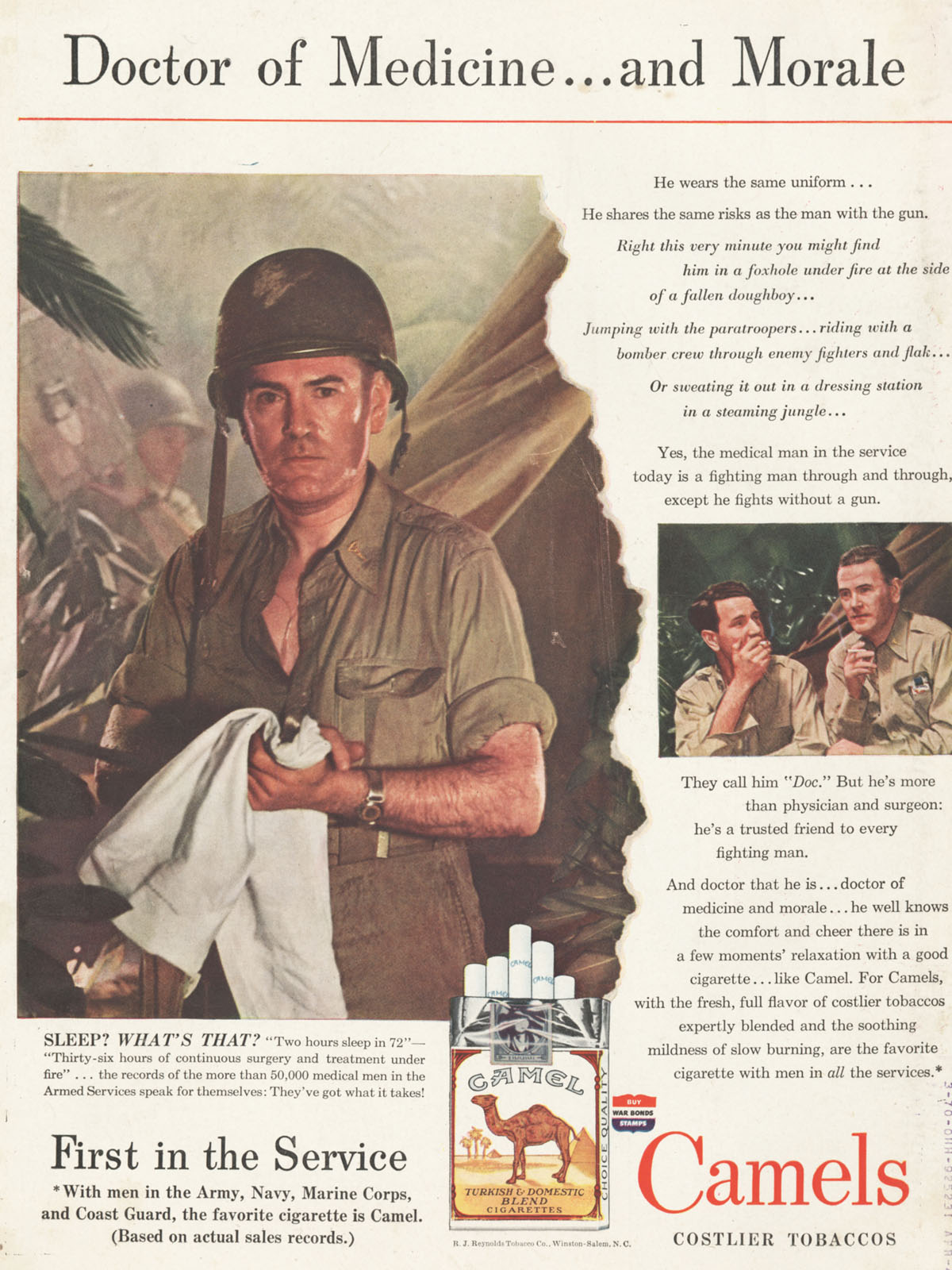

When my grandfather deployed to fight in Italy and North Africa, cigarettes were a crucial part of the rations given to soldiers. If he was not a smoker before he left, I suspect the habit was well-ingrained by the time he returned. During the war, at home and abroad, tobacco advertisers worked hard to associate their brands with toughness and patriotism. Smoking on the front lines calmed the soldiers’ nerves and kept them awake during grueling watches. Troops traded cigarettes amongst themselves as a form of currency, and even distributed them to POWs to reduce the stress of a difficult situation.

The Greatest Generation paid a price for their tobacco addiction, and for their exposure to second-hand smoke. Many died unpleasant deaths from smoking-related causes at ages we would now consider relatively young. Their children, the Boomers, witnessed this carnage, then pushed through laws that resulted in an astounding reduction in smoking rates across the developed world. Twenty years ago, I recall measures to ban smoking in Irish pubs and French cafés being roundly mocked for their predicted futility. But in the end, the protests fizzled.

It turned out people liked being able to breathe clean air. And as the number of smokers decreased, their influence waned, and even stricter measures passed without major opposition. But this success only arrived after many determined individuals and forward-thinking governments spent decades battling billion-dollar tobacco corporations and the habits of the deeply addicted.

The cigfluencers cashing in on Instagram and TikTok today presumably have no memory of any of this. They were born into a world where smoking was already a rare curiosity. Their followers seem to view a cigarette as a fashion accessory. And when a young character in a movie or TV show lights up to increase his gravitas, the smoke from his cigarette stays safely on the other side of the screen: the perceived coolness transmits, the negative effects do not.

Has the very success of the anti-smoking movement sowed the seeds of a potential cigarette revival in those too young to remember how hard the battle was?

Smoking is only one manifestation of what seems to be a trend of societal forgetfulness. In recent years, various other horrors once presumed safely in the past have returned to haunt us, including exciting classics like polio and fascism. The reasons suggested for their resurrection are numerous. Is it nostalgia gone wild? Misinformation and disinformation? A pandemic-induced pushback against all public health advice? Social media brain rot?

Collectively, humans have never been very good at learning from the mistakes of our past, but social media and online news seems to be accelerating the problem. Inundated with reams of content, we obsessively refresh our feeds for the latest updates, but we have little patience for anything that happened last week, let alone last decade or last century. Our educational systems are not helping. In 2023, student testing in the US showed that only 13% of 8th graders were considered proficient in history. What once-common knowledge will these students lack as they grow older?

Over three generations, we have gone from sacrificing millions of lives in the fight against Hitler and Mussolini, to happily voting for politicians who spout eerily similar rhetoric. Because the allies won the Second World War, the relative freedom that followed under successive democratic governments feels like a boring baseline, rather than the incredible exception to autocratic rule that it is. Our promises to never forget have already been forgotten, and at the soonest opportunity. I don’t believe it’s a coincidence that fascist and fascist-adjacent ideas are once again spreading into the mainstream just as the last of the Second World War veterans pass away.

During the same timeframe, we have gone from hailing vaccination as one of humankind’s greatest achievements, to declaring the entire practice a fiction, a danger, or even a conspiracy. The diseases are real. I have met people my age who still walk with braces in their shoes after childhood bouts with polio, contracted from encounters with other unvaccinated children. Smallpox, measles, diphtheria, tuberculosis: diseases that once struck fear into people’s hearts are for now just archaic terms from the past, thanks entirely to routine vaccinations. But only smallpox has been permanently eradicated, and the rest wait patiently for an opportunity to spread again in an unvaccinated populace.

That childhood mortality rates have plummeted from roughly 50% to nearly zero over the past century is a miracle that is now taken for granted. As with the anti-smoking movement, these vast successes obscure the fact that our current normal did not come about by accident.

Humans have lived through these dark realities already. To return to them, not just accidentally or blindly, but with salivating enthusiasm, would be a staggering example of mass amnesia. But like a young smoker taking her first tentative puff on a cigarette, the ramifications will unfold over many years. By the time the impacts of our current forgetfulness are clear, it may be too late.

References

Barrington-Trimis, J. L., Urman, R., Berhane, K., Unger, J. B., Cruz, T. B., Pentz, M. A., Samet, J. M., Leventhal, A. M., & McConnell, R. (2016). E-Cigarettes and Future Cigarette Use. Pediatrics, 138(1), e20160379. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0379

Field, M. (2022, September 16). Polio is back in the United States. How did that happen? Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2022/09/polio-is-back-in-the-united-states-how-did-that-happen/

Henderson, D. A. (1997). The Miracle of Vaccination. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 51(2), 235–245.

Mapped: Europe’s rapidly rising right. (2024, May 24). POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/mapped-europe-far-right-government-power-politics-eu-italy-finalnd-hungary-parties-elections-polling/

Mendes, E. (n.d.). The Study That Helped Spur the U.S. Stop-Smoking Movement. Cancer.org. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/the-study-that-helped-spur-the-us-stop-smoking-movement.html

Mervosh, S. (2023, May 3). It’s Not Just Math and Reading: U.S. History Scores for 8th Graders Plunge. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/03/us/us-history-test-scores.html

Roser, M. (2024). Mortality in the past: Every second child died. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past

Rufo, Y. (2024, November 2). Are celebs such as Charli XCX and Addison Rae making smoking “cool” again? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce8dy5v1kpno

Smokeless Joe. (n.d.). Bar Towel. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.bartowel.com/regions/pubs/smokeless.phtml

Tobacco Advertising Collection: World War II. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://tobacco.stanford.edu/cigarettes/war-aviation/world-war-ii/

Tobacco use declines despite tobacco industry efforts to jeopardize progress. (n.d.). Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news/item/16-01-2024-tobacco-use-declines-despite-tobacco-industry-efforts-to-jeopardize-progress

Wayne, B. (n.d.). Smoking in the Military: Resisting the Urge. Concordia Memory Project. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://concordiamemoryproject.concordiacollegearchives.org/exhibits/show/sartyessays/smoking

Werner, K. (2023, September 5). Timothée Chalamet faces backlash for smoking at Beyoncé concert. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/timothee-chalamet-smoking-beyonce-concert-b2405229.html

Comments ()