An American Nightmare

Fascism is on the rise. There is war in Europe. Americans are politically divided and culturally bereft. The year is 1940, and Henry Miller is going on a road trip.

“I was prepared to like Boston,” wrote Henry Miller in the introduction to The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. He was anticipating his return to America after a decade in Europe, but his optimism did not last. “When I came up on deck to catch my first glimpse of the shore line, I was immediately disappointed. Not only disappointed, I might say, but saddened.”

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare was Miller’s attempt to capture the cultural climate in America at the very beginning of the Second World War. In 1940 there was a collective sense of impending doom. 85 years later, with political division, simmering violence, climactic devastation, and economic hardship once again pressing in from every side, it might be a good time to see what we can learn from those who survived earlier hard times. Henry Miller’s obscure and unloved book might make for a useful, if somewhat pessimistic, guide.

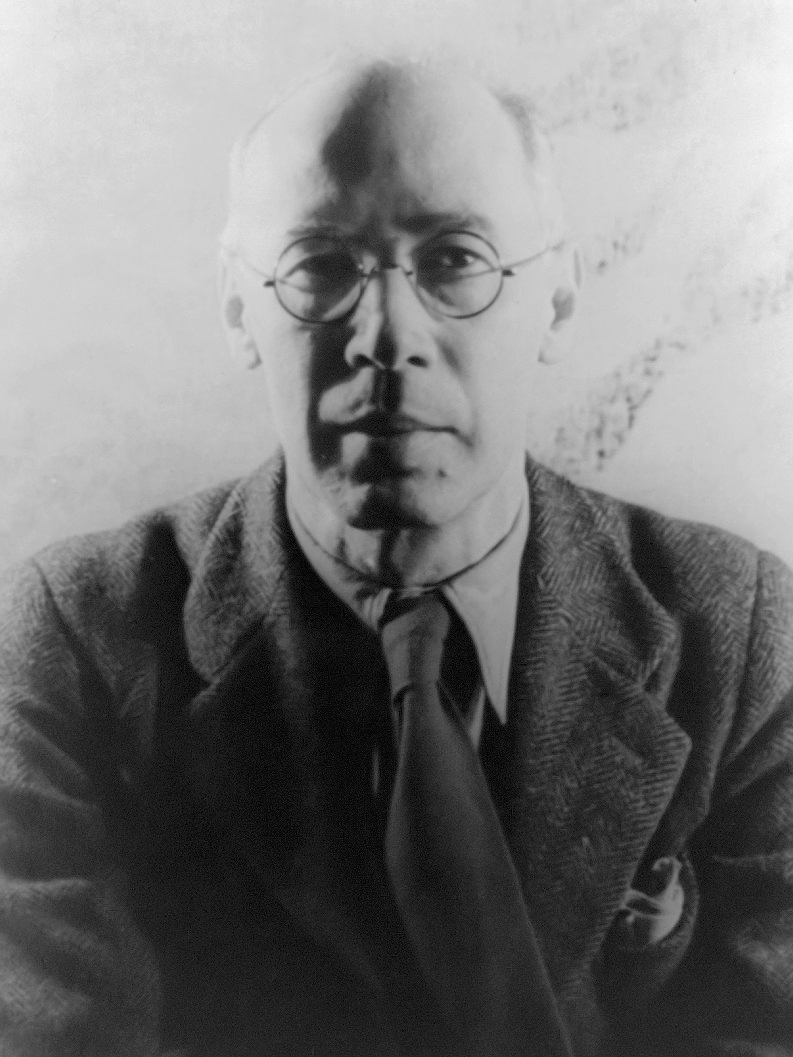

When Miller returned to the United States in 1940, it would be an understatement to say he was unimpressed by the country he found waiting for him. He deeply missed his former life as a bohemian expat in Paris, where he had surrounded himself with artists and writers, and where he had published his first books, including The Tropic of Cancer. Leaving France in 1939 ahead of the Nazi occupation, Miller spent nine months in Greece, where he explored the mainland and several islands, including Corfu, Crete and Hydra. There, Miller filled his days rambling around in the sunshine of ancient battlegrounds and temples, and his nights engaged in lively taberna debates with creative minds like British writer Lawrence Durrell and Greek intellectuals George Seferis and George Katsimbalis.

His Greece trip, also cut short by the looming war, had been transformative for Miller. Soon after returning to the United States he poured his rapturous impressions of Greece into The Colossus of Maroussi, an autobiographical book published in 1941. When asked what he liked so much about Greece, Miller said “The light and the poverty.” Accused of romanticizing the hardship of others, Miller was quick to defend his qualifications: “I can say that because I’ve been poor all my life.”

Back in New York City, Miller was dirt poor again, kept afloat only by the generosity of friends. There was demand for his earlier fiction books, but they had been banned in the United States for obscenity, and would remain banned until the 1960s. Those bans, along with the war already underway in France, meant he could expect no further royalty cheques. By 1940, Miller found himself facing a perfect storm of personal and global disaster. He was nearly 50, with little income and no savings. He was twice divorced, and isolated from his European friends. And he was watching his father slowly die in the hospital.

Events in the wider world did not cheer him up. France and Greece were both occupied by fascists, and the cities and ports of England were being bombed nightly. The United States was eying the situation warily, torn between an instinct for isolationism and a growing sense that, eventually, they would have no choice but to join the war – a fear eventually confirmed by the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. There was a general feeling that everything was about to get much worse.

Fresh from the cobblestones of Villa Seurat in Paris and the ancient landscapes of Greece, Miller now contemplated the hulking bridges, factories, and skyscrapers of modernizing America. He despaired at the polluted rivers and the slag heaps next to the mines. He detested the self-promoting, wheeling-dealing businessmen he encountered, obsessed with only one thing: making money. He had little confidence that Americans were psychologically prepared for war.

“Our world is a world of things. It is made up of comforts and luxuries, or else the desire for them. What we dread most, in facing the impending debacle, is that we shall be obliged to give up our gew-gaws, our gadgets, all the little comforts which have made us so uncomfortable.”

Unfortunately for Miller, most Americans did not not share his dismay about their burgeoning consumerism, nor were they as horrified as he was about the “stultifying labor” required to pay for the new automobiles that filled the factory parking lots. In fact, many Americans were delighted to find themselves gainfully employed after the Great Depression, and they were eager to spend on the newly available products Miller derided.

Miller’s revulsion of American consumption said more about his own artistic priorities than any objective reality. The Greece he loved so much was economically poor, but it sat on a bedrock of art and culture thousands of years old, and those were the assets Miller prized over cars and radio-phonographs. America, in contrast, was growing ever more prosperous, but in Miller’s view it lacked culturally significant artists, musicians, writers, and classical architects. It also lacked a populace that cared deeply about artistic endeavors, preferring the nascent pop culture of comic books and Bing Crosby.

Miller soon devised an escape from all this grim despair: a road trip across the United States. Traveling first south, and then west across the width of the country, Miller would seek out some of the unsung creative characters that populated America. Then, he would write a book about it.

“[T]here is a class of hardy men, old-fashioned enough to have remained rugged individuals, openly contemptuous of the trend, passionately devoted to their work, impossible to bribe or seduce, working long hours, often without reward or fame, who are motivated by a common impulse—the joy of doing as they please.”

Miller’s artist friend Abe Rattner agreed to join him on the first leg of the trip, to be funded by a $500 book advance from Doubleday and a small grant from President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) program.12 As soon as Miller completed “a half dozen lessons in driving” the two men set out in a temperamental 1932 Buick, passed through the Holland Tunnel, then headed south towards their first stop.3

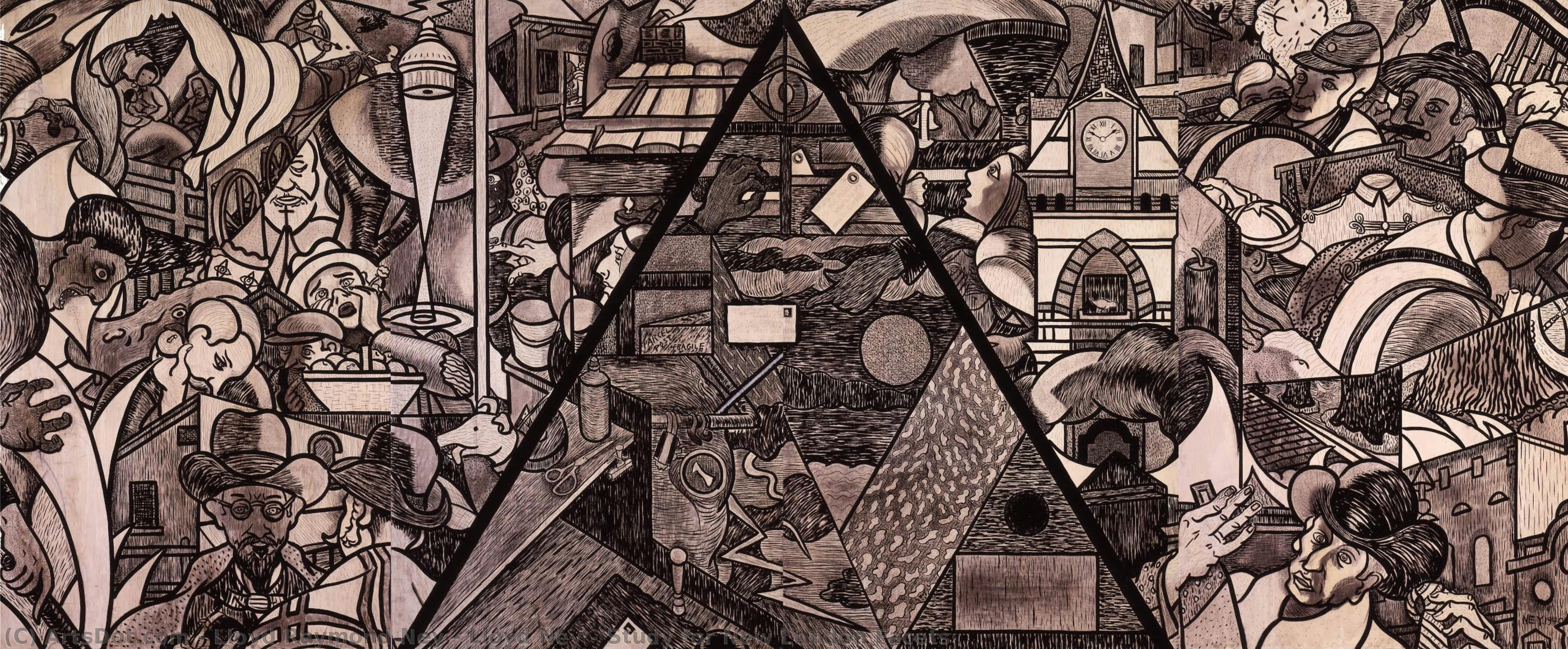

By the 1940s, New Hope, Pennsylvania had long been established as an artists colony. One of the town’s more feisty residents was the sculptor and painter Lloyd “Bill” Ney, who had traveled with Rattner in France at the end of the First World War. That trip had exposed the two artists to the work of Picasso and other modernists. But when Ney attempted to bring these newer ideas home, he found his more abstract work promptly rejected by the traditionalist New Hope art shows. In response, he launched his own Modernist exhibition. Later, Ney fought vigorously with stubborn gatekeepers to have his Modernist murals accepted for a public commission at the post office in New London, Ohio.

Miller admired Ney, and he left New Hope energized. But the hardscrabble life he saw many of the colony’s artists enduring also confirmed his assumptions about the status of non-commercial artists in the United States. “America is no place for an artist: to be an artist is to be a moral leper, an economic misfit, a social liability,” he wrote. “A corn-fed hog enjoys a better life than a creative writer, painter or musician.”

At New Iberia in Louisiana, the men stayed at the Shadows-on the-Teche plantation, an estate owned by William Weeks Hall, another painter friend of Rattner. Hall felt duty-bound by the plantation and the responsibilities he had inherited along with it, which included frequent interruptions to escort tourists around the historic property. His true passion was painting, but his ability to do so had been permanently hampered by an arm injury sustained in a car crash in 1937.

Hall had his own ways of coping. Late one night, he showed Miller a secret: it was a device he called a “magic lantern,” which he used to project abstract patterns of colourful light onto blank canvases in a darkened room. This magic lantern, Hall insisted, provided him with more visual euphoria than his paint and brushes ever did. Perhaps he would not need his painting arm after all?

Exploring the Louisiana plantation house, Miller also encountered artwork from an earlier era, in the form of peopled landscapes by Marie Adrien Persac. Miller described Persac, who was born in France in 1823, as an itinerant painter, though his biography suggests he was something more than that. Miller, in his typical style, seized on a few thin facts and proceeded to create his own mythology: in this worldview, Persac was not merely a competent landscape painter, but rather an idealized personification of an artist, one who traveled from place to place and enjoyed warm southern hospitality in exchange for his creativity. Those now-gone days of the previous century, Miller conjectured, marked a time when the contributions of artists were truly appreciated in America.

In nearby New Orleans, Miller and Rattner visited Dr. Marion Souchon, a surgeon who was still performing operations in his 70s, even as he began to take his hobby of painting more seriously. Souchon churned out what a Time magazine article described as “Van-Gogh like pictures” of Louisiana landscapes and interiors.4 He painted at a furious pace, as if making up for lost time.

Miller interrogated Souchon about the transition from surgeon to painter, and the ongoing coexistence of these two demanding practices. Souchon did not regret dedicating so many decades to medicine. “Surgery is science and art combined, and for that reason it satisfied, for the time being, the urge for art,” he said. But he did admit, to Miller’s great satisfaction, that the more he painted, the more painting took precedence over other aspects of his life.

And Souchon’s interest in art was hardly a new whim: he had painted, drawn and sculpted throughout his childhood and into early adulthood, then set those interests aside for decades to focus on his career. Now in his old age, he was closing the circle, applying the physical and emotional skills he had honed as a surgeon to this new medium. In his mind, creativity was not limited to the art studio.

In New York City, Miller was exposed to the music of composer Edgar Varèse, played aloud on a “magnificent recording machine”. Born in France, Varèse had emigrated to the United States during the First World War. Miller describes Varèse’s compositions as “cacophonous” and “nerve-wracking” and “dissonant”. In an interview, Varèse himself explained why he preferred to call his audio creations “organized sound” rather than music:

“As the term ‘music’ seems gradually to have shrunk to mean much less than it should, I prefer to use the expression ‘organized sound,’ and avoid the monotonous question: ‘But is it music?’ ‘Organized sound’ seems better to take in the dual aspect of music as an art-science, with all the recent laboratory discoveries which permit us to hope for the unconditional liberation of music…”

The sheer novelty of Varèse’s sound provided Miller with an opportunity to excoriate Americans for their timid taste in art of all kinds. “Aesthetically, we are probably the most conservative people in the world,” he wrote. “[W]e are incapable of enjoying something new, something different, until we are first told what it’s about.”

Speaking with Miller, Varèse discussed his desire to evoke the sounds of the Gobi Desert, an idea that foreshadowed Déserts, a composition he would release in 1954. Varèse was ahead of his time: when new technology for audio recording and electronic music production became viable, he embraced it. In the 1940s and 1950s, this was an experimental choice, but today it’s hard to find any music that hasn’t been manipulated electronically to some extent.

Later in his trip, Miller visited San Francisco, but the city did not make a positive impression on him. He was, however, moved by the murals of painter Hilaire Hiler. Much like the surgeon painter Souchon, Minnesota-born Hiler was something of a polymath – in addition to a muralist, he was also a competent piano player, a nightclub owner, and a psychoanalyst who spent time with patients at the St Anne’s psychiatric hospital in Paris.

Hiler’s murals are in the Aquatic Park Bathhouse Building. Depicting a colourful, psychedelic, and slightly cartoonish underwater dreamscape, the paintings look to modern eyes like backdrops for an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants. Both the building and its murals, completed between 1938 and 1939, were paid for by Roosevelt’s WPA, the same New Deal program that helped fund a small portion of Miller’s road trip. When the murals were restored to their original vibrancy in 2010, historical geographer Gray Brechin said the process was a reminder that the Great Depression was not all grey and dreary. “I have realized that it was a very hopeful time. It really inspired leadership that people felt cared for them,” he said – a cozy sentiment that I suspect Miller would have torn to shreds.

If Miller’s road trip was to be judged solely on his ability to dig up inspiring examples of creative minds at work in the United States in the early 1940s, then it could be declared a success. The conformity and consumerism Miller observed on the surface of American society was not ubiquitous. The independence of Americans was firmly intact in positive ways. Though the creators Miller visited were clearly influenced by trends in Europe, they made art that was anchored in the American geography and mindset.

But none of these artists became household names. And outside the art world, Miller’s pessimism about America was not unwarranted. He found much to criticize, including environmental degradation, the gap between rich and poor, and the racist treatment of Black and the Indigenous peoples (though he scarcely wrote about women, and he did not visit any women artists). Miller’s choice of language was not that of a modern day progressive, but his ideas of right and wrong were clearly defined and unwavering.5 In his view, the myth of America’s founding, and the later push westward, was as cruel and violent as the religious persecutions early Americans had supposedly fled in Europe. He was not fooled by patriotic propaganda.

“One of the curious things about these progenitors of ours is that though avowedly searching for peace and happiness, for political and religious freedom, they began by robbing, poisoning, murdering, almost exterminating the race to whom this vast continent belonged. Later, when the gold rush started, they did the same to the Mexicans as they had to the Indians.”

Near the end of his trip, Miller found himself an unlikely guest at a dinner party in Hollywood, surrounded by a menagerie of rich, neurotic, and very drunk guests. The dinner devolved into a free-for-all shouting match of overlapping political arguments. One man was infuriated by the idea that the United States should join the war in Europe. “We're not fighting to hold the British Empire together,” he shouted, before demanding that a Canadian woman go back to England. Soon he was on his feet, ready to throw punches at another man for the sin of daring to insult President Roosevelt. In the end, Miller fled the party to explore the exotic Californian night alone, drunk, and on foot.

When Miller submitted his manuscript for The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, Doubleday rejected it. By then it was wartime, and books and movies were expected to unify Americans for the fight ahead. Patriotism was in demand, and scathing social criticism was a hard sell.6 When the book was finally published by New Directions in 1945, as the war ended, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare was not successful.

But time has vindicated Miller. The fractures and flaws he identified in America over 80 years ago have not faded – if anything, they have intensified. The gap between rich and poor has widened. The wealth and political power of today’s tech moguls probably exceeds that of the old industrialist robber barons and Second World War profiteers. Anti-intellectualism remains proudly at the center of American culture, which has been exporting reality TV and auto-tuned pop music for decades. Generative AI, America’s newest shiny “gew-gaw,” is threatening to wipe out the livelihoods of writers and visual artists alike, in a way that even Miller could not have imagined in his most surrealist literary hallucinations. Reading The Air-Conditioned Nightmare today is both alien and familiar: the specific references are dated, but the themes are depressingly current.

After the war, Miller settled in California. First he set up shop in Big Sur, where he played host to a stream of counterculture figures, inspiring the beats and the hippies in turn. When his fame and age made that existence difficult, he retreated to a more stately home in the Pacific Palisades area of Los Angeles, where he lived until his death in 1980 at the age of 88.

In January 2025, as I was writing this, wildfires roared through the Los Angeles region, devastating multiple areas, including the Pacific Palisades. The destruction stopped just a few doors away from Miller’s former house, which still stands at 444 North Ocampo Drive. But like Miller’s road trip, that narrow escape feels more like a temporary reprieve from reality than a happy ending. America’s nightmares are far from over.

A full text version of The Air-Conditioned Nightmare by Henry Miller is available to read for free on Archive.org [PDF].

References

Adrien Persac (n.d.). Facts about Adrien Persac. askART. Retrieved January 18, 2025, from https://www.askart.com/artist/Adrien_Persac/68512/Adrien_Persac.aspx

Alterman, J. M. (n.d.). New Hope Art Colony/Pennsylvania Impressionism. askART. Retrieved January 18, 2025, from https://www.askart.com/art/Groups/132/y/New%20Hope%20Colony

Art: Painting Doctor. (1941, December 29). Time. https://time.com/archive/6770512/art-painting-doctor/

Edgard Varèse. (2024, December 18). Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edgard-Varese

Emma Goldman (1869-1940). (n.d.). PBS American Experience. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/goldman-1869-1940/

Franchini, G. (2010, July 19). Restored Depression-era maritime murals recall heyday of public art. San Francisco Public Press. https://www.sfpublicpress.org/restored-depression-era-maritime-murals-recall-heyday-of-public-art/

Harry Truman and the Investigation of Waste, Fraud, & Abuse in World War II. (n.d.). Levin Center for Oversight and Democracy. Retrieved January 18, 2025, from https://levin-center.org/harry-truman-and-the-investigation-of-waste-fraud-abuse-in-world-war-ii/

Holmes, T. (2020). Edgard Varèse and The Listener’s Experiment. Taylor & Francis. https://uat.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780429425585-15/edgard-var%C3%A8se-listener-experiment-thom-holmes

Leary, W. M. (1968). Books, Soldiers and Censorship During the Second World War. American Quarterly, 20(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711034

Lloyd Raymond Ney—Lloyd Ney—Study for New London Facets. (n.d.). ArtsDot. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://en.ArtsDot.com/@@/D5GJDC-Lloyd-Raymond-Ney-Lloyd-Ney--Study-for-New-London-Facets

Marion Souchon. (n.d.). 64 Parishes. Retrieved January 18, 2025, from https://64parishes.org/entry/marion-souchon

Miller, H. (1945) The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. (New Directions)

Miller in Paris. (2013, November 30). Aller Retour Paris. https://henrymillerlibraryparis.wordpress.com/henry-miller/

Palisades Fire Damage Maps. (n.d.). Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://recovery.lacounty.gov/palisades-fire/

Precipotato (Director). (2019, August 9). Edgard Varèse—Déserts [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cnEo7-g880

Prescott, O. (1945, December 19). Books of the Times. New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.nytimes.com/1945/12/19/archives/books-of-the-times-genius-to-a-tiny-cult-some-things-author-likes.html

Syriopoulou, L. (2018, May 18). Henry Miller: On friendship, light and a paradise lost in Greece. Greek News Agenda. https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/henry-miller-on-friendship-light-and-a-paradise-lost-in-greece/

The Shadows. (n.d.) William Weeks Hall Era. Retrieved January 19, 2025, from https://www.shadowsontheteche.org/history/william-weeks-hall-era

Works Progress Administration (WPA). (2022, September 21). History. https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/works-progress-administration

Zanello, M., Pallud, J., Baup, N., Peeters, S., Turak, B., Krebs, M. O., Oppenheim, C., Gaillard, R., & Devaux, B. (2017). History of psychosurgery at Sainte-Anne Hospital, Paris, France, through translational interactions between psychiatrists and neurosurgeons. Neurosurgical focus, 43(3), E9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.6.FOCUS17250

Between 1927 and 1946, the publisher we now know as Doubleday was actually called “Doubleday, Doran”. ↩

The WPA (which first stood for Works Progress Administration, and later Works Projects Administration) was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, a series of public spending programs intended to counteract the Great Depression. ↩

Though not overtly acknowledged in the book, Miller’s “road trip” was not really contiguous. He interrupted it at least once to fly back to New York City, and then resumed the trip at a later date. ↩

There are a few of Souchon’s paintings online, but none in the public domain. Spoiler: they don’t look particularly exceptional to modern eyes. ↩

Miller’s politics were strongly influenced by seeing anarchist organizer Emma Goldman, speak at an event when Miller was a young man. Jailed and deported from the US for her role in an attempted assassination and interfering with draft registrations, Russian-born Goldman eventually died in exile in Toronto in 1940, several months before Henry Miller’s road trip began. ↩

In his article Books, Soldiers and Censorship During the Second World War regarding books sent to soldiers on the front lines, author William M. Leary, Jr. states: “The mere process of selecting titles involved a form of censorship. The Council… would not approve books that contained statements or attitudes offensive to our Allies…” ↩

Comments ()